My review of this book is now up on Butterflies and Wheels.

Archive for June, 2008

Heat and Light: Christopher Hitchens and His Critics

June 30, 2008On Chesil Beach

June 29, 2008Again: spoiler alert

I have just read Ian McEwan’s On Chesil Beach. I was expecting long, drawn-out awkward negotiations – like a novella-length episode of Peep Show. Thankfully, it’s not like that and much of the narrative consists of Edward and Florence’s past and future lives. We could have done with more insight into Florence’s life, and her perspective, but this is one of the flaws of the novel.

The story centres on one couple’s wedding night in the pre-liberation early sixties. Edward, the groom, is looking forward to the consummation: Florence is not. I don’t want to spoil the story, but she makes a counterproposal to Edward – she wants to be married, but doesn’t want sex, and is happy for Edward to make love to other women as long as the marriage remains legitimate and she does not have to submit to him in the bedroom.

The groom is not impressed with this and anulls the marriage. It’s only years later when Edward, having become a libertine, realises that Florence’s idea is completely reasonable, the kind of interpersonal deal that he and his soixant-huitard friends made all the time. On Chesil Beach is an insight into the follies of puritanism: how, rather than eradicate the sexual instinct, it magnifies it to a morbid and fantastical degree.

For a completely insane alternate reading of the novel, see Ellis Sharp.

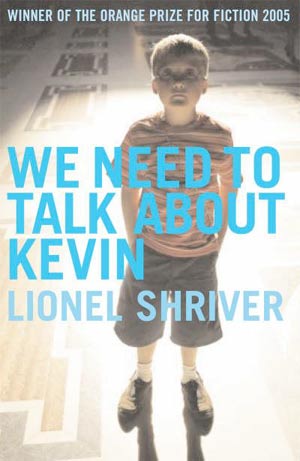

Classic Books: We Need To Talk About Kevin

June 28, 2008 The secret is that there is no secret.

The secret is that there is no secret.

We Need To Talk About Kevin, Lionel Shriver, Counterpoint 2003

Warning: spoiler alert

What do you do if you don’t actually like your children? And what happens if your offspring grows up to become a killer? These are the questions posed in Shriver’s blistering novel on murder and motherhood.

The novel generated a great deal of controversy – in a delightfully cheesy summation, the Belfast Telegraph said that: ‘Maybe we all need to talk about Kevin.’ I sense that this controversy stems not so much from the choice of school shooting as subject matter, but in Shriver’s challenging of the view that parenthood is always and everywhere the right thing. In the interview I’ve linked to above, Shriver says this:

I think that parents feel to give voice to what they don’t like about parenthood is to betray their children and that is why I found a number of woman, in particular, have been grateful for this book. It’s someone giving voice to his or her reservations. And Eva speaks for them about the things that they have never felt they had permission to say.

Eva Khatchdourian doesn’t like her son, and she doesn’t like the idea of procreation to start with. By thirty-seven she has built a fortune on her business producing Rough Guide-style travel books, and is the epitome of the self-made career woman. She agrees to childbirth in deference to her husband, the wholesome, musclebound Reaganite Franklin. Franklin is such a caricature of the American Dad that he almost – but not quite – becomes fantastical parody. In love with the idea of fatherhood and the family life, he adores Kevin and goes to great lengths to place the best possible interpretation on his son’s misdeeds.

In a criticism of the novel, one reader described Kevin himself as ‘a monster, the spawn of Satan like Damien in The Omen. He has the manipulative, divisive intelligence of a criminal from the moment of his birth.’ It’s true that Kevin appears sociopathic from almost day one. In addition to murdering eleven people, he destroys cherished possessions, sabotages property, gets a teacher fired and burns out his sister’s eye with bleach.

Evil has many facets and the impression we have of Kevin is not so much active malice as a ferocious, uncompromising indifference. He has almost no interests, no friendships, no desires – indeed, he has contempt for the very idea of interests and desires. Kevin’s selected victims have one thing in common – they are all passionate about something; politics, sports, drama. Not content with being desireless himself, he seeks to punish people for having desires.

To characterise as monstrous implies fantasy, yet I found Shriver’s portrayal of Kevin chillingly realistic. (Indeed, Shriver says she gets letters claiming that ‘We have a Kevin’ – prompting the author to quip that she began to fear leaving the house.) The name itself recalls Harry Enfield’s comedy adolescent. I’m only eighteen months older than Kevin, and I see in him our generational tics and affectations. The obsession with pop culture, not for enjoyment thereof but as a means of keeping score. The use of prejudice and epithets purely to get a rise out of someone. Most of all, the pretence of jaded experience, of having seen it all before. Like Kevin, I used to respond to every new fact with ‘I know.‘ ‘How can you know so many things, you’re a kid,’ my father once said, in justified exasperation.

The novel hinges on the classic nature/nurture debate: was Kevin born evil or is his crime a reaction to an uncaring mother? And Eva clearly loves his sister more. His father loves not Kevin but the idealised persona of the Little League son that he constructs in spite of KK’s true nature. In turn, Kevin creates his own persona: ‘Kevin is his own construct,’ Shriver says. When Kevin is six, Eva breaks his arm by hurling him across a room – convinced that Kevin is dragging his feet over nappy training. Since Eva narrates, we have no choice but to perceive events through her eyes, although many of Kevin’s minor atrocities are open to ambiguity and alternate interpretation. (And son and mother are alike in many ways: their looks, arrogance, sense of superiority.)

Near the end of the novel, Kevin is interviewed in his cell as part of a documentary. The journalist asks about his relationship with his mother. Watching the programme at home, Eva expects to be denounced and is shocked when, instead, he praises her career achievements. ‘Lay off my mother… Shrinks here spend all day trying to get me to trash the woman, and I’m getting a little tired of it, if you wanna know the truth.’ Eva also sees, on a wall of Kevin’s cell, a photograph of her that went missing years ago and that she thought her son had destroyed. ‘I guess I’ve always assumed the worst,’ Eva admits.

There’s also the point where a ten-year-old Kevin falls sick and becomes friendly and responsive, actually taking an interest in his surroundings. It takes a lot of energy, Shriver says, to generate that outer, cynical, sophisticated self that many teenagers, and adults, fabricate.

Everyone is constantly asking Kevin why he did it, and Shriver rejects all conventional explanations. News stories about other high school massacres recur again and again in the novel, like a background hum. Four years after the book was published, there was a university shooting, courtesy of twenty-three year old Cho Seung-Hui. Eva’s recurring complaint is that no one in America takes responsibility for anything, and that people apportion blame on anyone and everything except the individual who pulls the trigger.

It’s not a crime of passion. Kevin plans the massacre meticulously, even researching his defence in advance (and managing to secure a lenient seven years). He takes care to differentiate his crime from the dozens of others – there is no note, no videotape explaining his social alienation, no Marilyn Manson CDs. You can’t even blame the NRA, because Kevin kills with crossbow, not firearm – a way for both Shriver to avoid political simplicity in her novel and for Kevin to avoid giving ‘bien pensant liberals like [Eva] yet more evidence for their favoured cause of tighter gun control.’ It’s this urge to differentiate himself that is the only clue to Kevin’s motive: when Eva asks why he didn’t murder her as well, Kevin replies that ‘you don’t kill your audience’. And he’s outraged when Klebold and Harris upstage him only ten days after his own atrocity.

Our last encounter with Kevin comes as he is awaiting his eighteenth birthday, and transfer to an adult prison. Visiting her son in juvenile hall, Kevin presents her with his sister’s glass eye, which he has been keeping safe for two years. ‘It was like she was, sort of, looking at me all the time. It started to get spooky.’ Eva replies: ‘She is looking at you, Kevin… Every day.’ This is a beautifully constructed scene, both macabre and touching.

In it Kevin seems human. In this podcast, Shriver says:

I was hoping to portray this as strength… It’s only as he’s turned eighteen and he’s looking at manhood, and manhood in an adult prison, that he becomes a boy, and he embraces his own naivety and his own youth. For Kevin, getting smart is realising that he’d been an idiot, so you know he’s gone through all these different justifications of why he did what he did and they grow more and more sophisticated in one way, but real sophistication is coming to the end of all that and realising that he had no idea why he did what he did, and for Kevin being utterly mystified is really, that’s when he gets it, that’s when he’s grown up, that’s when he’s sophisticated, when he is confused by himself. It’s when he thinks he understands himself that he’s being fooled.

Shriver finishes with, if not redemption, then the hope of redemption in the future. It’s significant that hope comes when Kevin turns eighteen: the message, perhaps, is that we all at some point have to put away our childish and deadly toys.

Sharia for mercenaries

June 27, 2008Now this is weird. Why would a mercenary company run by a bunch of crazed Christian theocons want one of its lawsuits to be settled by Sharia law?

Especially since Blackwater seem to have a cavalier attitude to local laws in the Middle Eastern countries in which it operates.

Well: because Blackwater’s founder, Erik Prince, is being sued by military widows after a plane carrying US soldiers – from an airline owned by Prince – crashed in Afghanistan.

If the judge agrees, it would essentially end the lawsuit over a botched flight supporting the U.S. military. Shari’a law does not hold a company responsible for the actions of employees performed within the course of their work.

Handy that.

As the Seattle Post-Intelligencer says: ‘The actions of Blackwater employees indicate that the law matters little to the company, but really, they’ll go with whatever frees them from accountability.’

Thwaite arrives

June 26, 2008Mark Thwaite has been nominated for something called the Hospital Club 100 – ‘the true stars of London’s creative industries and the powers behind the throne.’

You can vote for him here, in the ‘Publishing’ category, until Monday July 7. (Mischieviously, I note that Ian McEwan is also a nominee).

It’s a far cry from his inclusion on 3am’s list of 50 Least Influential People in Publishing.

Seriously though – I used to review for Mark and he runs a great site. One of its many pleasures is in coming across fantastic books from independent publishers which you’d never pick up in the normal course of things. We agree on almost nothing, but I visit the site daily, and so should you.

Big Allah is watching you

June 25, 2008I’m loving Big Brother at the moment. It’s very funny to watch, and I’m fascinated by the way that the editors manage to forge a narrative out of 24 hours of material: creating order from life’s chaos.

If you’ve been watching you may remember the row between chilled-out Mohammed and the crazed Alex De Gale, later removed from the house for making sinister threats against the other contestants.

It was Mohammed’s birthday and he had a cross-dressing party. Alex upbraided him for this, saying it was against their religion – is there a Koranic line on tranvestism?

This is Johann Hari’s take:

If you were told the biographies of Big Brother contestants Mohamed Mohamed and Alex De-Gale, you wouldn’t find it hard to guess which one is the fundamentalist. Mohamed was born in Somalia in 1985. When he was five years old, he saw his mother being held at gunpoint, and thought she was going to die. Since then, he has spent most of his life fleeing from one civil war to another – until, finally, he was granted asylum in Britain. De-Gale was born in the same year in south London, to black British parents. She is now a lithe accounts executive with high cheekbones, short skirts, a BMW, and a seven-year old daughter she brings up on her own.

You guessed wrong. They wouldn’t use these terms, but Mohamed became a convinced secularist on the run from Somalia, while Alex learned a Wahhabbi interpretation of Islam on the streets of Tottenham. This emerged, as everything does on Big Brother, through a thicket of trivia. Mohamed’s birthday fell a week into his stay in the Big Brother house, so the producers threw him a party, and let him pick the theme. Remembering a fun night he’d had at university, he said he wanted the male housemates to dress as women, and vice versa. Everyone cheered and howled for alcohol.

Except Alex. ‘First and foremost,’ she said, ‘I am a Muslim.’ And that meant the idea of a man dressing as a woman ‘made me feel sick’. Jabbing her finger and shouting, she said to Mohamed: ‘Tell it to Allah [that] it’s all in the name of fun. It’s bad enough that we drink and smoke … You’re supposed to be a Muslim man, someone I can look up to for guidance. You will have my friends and family in uproar. I am disgraced by you … 85 per cent of the people I know are Muslims. And trust me – the sheer horror they would have experienced … [You have] disgraced Islam.’

‘You can’t tell me I’m a bad Muslim,’ Mohamed replied. ‘I am old enough to be responsible for myself. Don’t bring religion into it!’ She snapped back: ‘It is! There’s nothing else!’

Alex believes that Islam offers Absolute Judgements, immutably cast in stone in the Koran. These are (of course) hellishly patriarchal, since they were formulated by illiterate desert merchants in the seventh century AD. She has been taught there is ‘nothing else’. Later, she explained to another housemate that Islam forbids drinking and smoking. ‘What can you do then?’ he asked. ‘Pray.’ That’s all. If you see somebody acting in a way your pre-modern system judges to be ‘sick’ is it perfectly moral to threaten to kill them?

Mohamed, by contrast, sees the religion as consisting of metaphors and moral guidance – and he thinks it has limits. There are places it shouldn’t go. ‘She always brings religion into an equation that religion has nothing to do [with],’ he said angrily.

This reminds me of an article on the ‘Muslim refuseniks’ Irshad Manji and Ayaan Hirsi Ali. While they6 have similar positions, Manji is still a practicing Muslim while Hirsi Ali is a fierce unbeliever. Paul Berman has said that this is because Manji was brought up in liberal, secular British Columbia, whereas Hirsi Ali (like Mohammed) fled fundamentalist Somalia: ‘Ms. Manji offers her own support for Mr. Berman’s conjecture: ‘Had I grown up in a Muslim country, I’d probably be an atheist in my heart.’

All this may not prove anything, except that religion is perhaps best appreciated at a distance.

Succour London event

June 24, 2008Yeah, there’s a London launch – at the Poetry Cafe, Betterton Street, on Saturday July 5, 8pm.

A line-up featuring some of the UK’s most talented writers read their work from ‘Animals’, the new issue of Succour.

With Joe Dunthorne, Isobel Dixon, Lee Rourke and special guests.

Free entry!

And thanks to everyone who came to the Briton’s Protection launch on Friday – you made it a great night.

The devil wears Primark

June 24, 2008Sadly, that’s not a title I thought of but the title on a documentary on the company’s hideous employment and contracting policies – pulled by Channel 4 at the last minute.

But these things always come out:

A major industry needing child labour is sequin and Zari work, intricate embroidery immensely popular in America and Europe. Children’s thin, nimble fingers can work quicker on intricate ethnic designs. But by the time the youngsters engaged in the Zari sector reach their mid-teens, their hands and eyesight are often badly damaged by long hours of tedious work in dark rooms.

Their growth is often stunted by years of sitting in uncomfortable, hunched positions at the bamboo-framed workstations. The child workers have no fixed hours of work, nor is there any trade union to fight for their cause. For those who get paid at all, the combined wages of five children is less than that of one adult.

‘I go to a house in the camp every day,’ said Mantheesh. She sat in waist-high piles of Primark garments, many with labels and reference tracking numbers showing their destination in the UK and Ireland. ‘Sometimes we get major orders in and we have to work double quick. I am paid a few rupees for finishing each garment, but in a good day I can make 40 rupees (60p). The beads we sew are very small and when we work late at night we have to work by candle – the electricity in the camp is poor.’

Also, see Lucy Siegle:

In an industry of scant transparency, you can imagine how difficult it is for the handful of journalists who operate in this area to get solid evidence of exploitation. And yet they unearth horror stories with alarming regularity. This leads me to the depressing conclusion that the stories we see represent the tip of the iceberg rather than the exceptions.

If these ‘abuses’ are just a reality of today’s outsourced, mass-market rag trade, then it’s time retailers told us. How about a label in the must-have sun dress that reads: ‘We have absolutely no idea who made this garment because all production was outsourced to low-cost suppliers in Asia.’

The obvious becomes shocking

June 23, 2008I don’t want this blog to turn into ‘Mitchelmore Watch’. But our old friend at This Space has surpassed himself with another attack on – oh, you’ll never guess – Ian McEwan.

What mischief has the old rogue got into this week? Well, it seems that McEwan has given an interview to an Italian newspaper, Corriere della Sera, in which he says the following:

I myself despise Islamism, because it wants to create a society that I detest, based on religious belief, on a text, on lack of freedom for women, intolerance towards homosexuality and so on – we know it well.

Fairly obvious point and principle. I can’t find the interview online, but this is how the Independent reported it:

The novelist Ian McEwan has launched an astonishingly strong attack on Islamism, saying that he ‘despises’ it and accusing it of ‘wanting to create a society that I detest’. His words, in an interview with an Italian newspaper, could, in today’s febrile legalistic climate, lay him open to being investigated for a ‘hate crime’.

I’m not sure how prone to surprise you have to be to be ‘astonished’ that someone is against a far-right totalitarian ideology – and I’m no lawyer but how exactly would McEwan be charged with a ‘hate crime’ for saying the above?

This is not Amis redux. McEwan – at least in the piece that Mitchelmore and I link to – does not make anything like the appalling suggestions for which Amis has been rightly criticised. He can’t even be accused of singling out Islam:

McEwan’s interviewer pointed out that there exist equally hard-line schools of thought within Christianity, for example in the United States. ‘I find them equally absurd,’ McEwan replied. ‘I don’t like these medieval visions of the world according to which God is coming to save the faithful and to damn the others. But those American Christians don’t want to kill anyone in my city, that’s the difference.’

He also says this:

As soon as a writer expresses an opinion against Islamism, immediately someone on the left leaps to his feet and claims that because the majority of Muslims are dark-skinned, he who criticises it is racist.

And again he does no more than state the obvious. There is a section of the left that sees atheism as racism, and is astonished by common sense.

Nevertheless, the astonishment appears to be shared by Richard ‘Lenin’ Seymour and the ridiculous Islamophobia Watch site. Mitchelmore adds, ‘While Seymour answers better than anyone what McEwan says, I’ll take issue with what he doesn’t.’

Translation: I don’t know how to deal with McEwan’s stated arguments so I’ll make up imaginary arguments and attack those.

This is where we get to what I call ‘classic Mitchelmore’.

However ‘controversial’ Amis’s comments or ‘brave’ McEwan’s position on the indigenous culture of neo-colonies, both are red herrings. Nowhere in this interview does McEwan express any regret, let alone horror and shame, at his nation’s responsibility for the deaths of more than a million people in Iraq and Afghanistan… One would have thought the continuing aggression of the most powerful army in the history of mankind and its allies would be more pressing than media-enabled paranoia about a foreign religion.

As always: where to start, where to stop? Let’s begin with Mitchelmore’s grave theological error: conflating Wahabbi fundamentalism with Islam as a whole.

Fact: most of Al-Qaeda’s victims are Muslims. Indeed, they regularly blow up mosques, and even commit such atrocities during Ramadan. Islamism has almost zero support from Muslim communities, so why does Mitchelmore describe it as ‘the indigenous culture of neo-colonies’?

To suggest Islamism as ‘indigenous’ to Islamic countries is to buy into the BNP lie that all Muslims are terrorists.

He is on safer ground when it comes to civilian casualties in Afghanistan and Iraq. These indeed call for regret, horror and shame. But McEwan is no more responsible for civilian casualties than Mitchelmore himself. By Mitchelmore’s standards, anyone who pays tax in this country has blood on his hands. Should we all go around, Enfield-like, saying ‘I apologise for the conduct of my nation during the Iraq war?’ (Let’s leave the Medialens-style sneer at ‘media-enabled paranoia’ for now; surely we can agree that Islamism actually exists.)

It gets even better as Mitchelmore segues seamlessly from an attack on McEwan to an attack on… Prince Harry.

While McEwan asks for his fellow subjects to start “to reflect on Englishness: this is the country of Shakespeare, of Milton, Newton, Darwin”, he does not reflect that this is also the country of Prince “Bomber” Harry, a member of the English royal family involved in military attacks on civilians. During his time in Afghanistan, he is said to have guided fighter jets ‘towards suspected Taliban targets‘. In mitigation, McEwan can, with the rest of us, claim not to know what is really happening. After all, the London media that fawns over each of his claustrophobic and inorganic novels tends not to report that the ‘suspected Taliban’ are often women, children, wedding parties and even herds of sheep. (Maybe we’d hear more about it if they lived in tower blocks).

Well: for what it’s worth, I’m against the monarchy as an institution. Perhaps McEwan is too. Why not email him and ask? (And what is the ‘tower blocks’ reference about?)

And as for the comments about Englishness. What McEwan says is this:

‘Great Britain is an artificial construction of three or four nations. I’m waiting for the Northern Irish to unite with the Irish Republic sooner or later, and also Scotland could go its own way and become independent.’

Does the prospect disturb him? ‘No,’ he replied, ‘I think that at this point we should start to reflect on Englishness: this is the country of Shakespeare, of Milton, Newton, Darwin…’

Note to Mitchelmore: Ian McEwan is talking about devolution, which means independence from British rule. One would think the tireless anti-imperialist of This Space could get behind that.

And there’s a case for highlighting the positive aspects of English culture (the NHS, Orwell, Darwin) as well as the negative (imperalism, kingship, Peter Kay).

For some saner coverage, see David Thompson. Thanks: Harry’s Place, RSB.

Tireless cross-promotion

June 23, 2008Succour contributor Joe Dunthorne has a story in the Hamish Hamilton litmag, Five Dials.