Every man’s death diminishes us, it’s said. Narrator JJ has been diminished more than most. Their first great love, Thomas James, has died suddenly aged twenty seven. Now in Mexico City on a leap day JJ is moved to write the story of their affair.

Every man’s death diminishes us, it’s said. Narrator JJ has been diminished more than most. Their first great love, Thomas James, has died suddenly aged twenty seven. Now in Mexico City on a leap day JJ is moved to write the story of their affair.

Here’s another cliche: beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Thomas James is energetic and handsome but still, it’s hard to work out what JJ sees in him. Thomas is a photographer’s assistant obsessed with Morrissey and Soviet brutalism. He is cruel and bigoted. I don’t recall, from the dialogue, that he has a kind word for anyone. The nastiness of his behaviour and speech makes a nice ironic contrast with the tender lyricism JJ uses to describe him.

Perhaps it’s the attraction of opposites – a third cliche, but Martin Amis said that love makes cliches of us all. JJ as a person is everything that Thomas James is not – erudite, sensitive and politically engaged. They are by far the more interesting of the two lovers. Their narration is high camp with touches of modernism and religious grandeur – I felt at times I was reading the diaries of Teddy Thursby, Jake Arnott‘s dissolute peer of the 1960s. Wry observations end in assertions so pretentious they near make you laugh out loud. Take this: ‘SF is not a place, not really, it’s more a state of mind, an overlapping, a fault line from where you can hear the sighs of the unavenged Ohlone, Asia’s golden gates swinging open, the last startled gasp of the Viceroy.’ Or: ‘I’m sad that I’ll never get to see you in the newspapers collecting an award, and strike up a cigarette, startle my maid and mutter to myself, ‘Putain!’ with my eyes still full of desire.’ (JJ also says come as ‘cum’… transgressive, no?)

It is all in perception. Soon after Thomas has died JJ sees an artwork called Der Unfall at the Whitechapel gallery – ‘a strange turquoise black whirligig… four wagons colliding’ or ‘one wagon flying outwards in four directions’. The work’s ‘ominous logic and centrifugal force’ freaks JJ out, ‘as if the ominous white figure-eight at the centre of the accident were a void in which I was hurtling head-first.’ Near the end, a video work by Bruce Nauman provides much the same effect: ‘projectors threw the same image onto the floor and onto the wall in front of us, of two figures in black, rolling away from each other whilst reaching towards each other… They were two pairs of sirens, a quaternity, calling me into the whirlpool, like a deadly mirage composed of my own paranoiac desires.’

JJ was told by their mother that ‘I live my life like a sunbather in the park, forever moving the blanket to chase the sun’. JJ’s room in Mexico ‘never fully catches the sun’. Thomas’s bedroom has ‘a cantankerous set of vertical blinds that would never descend, so the room was never more than murky, with light spilling in from all the restaurants in the streets below.’ Falling into bed at dawn with a Californian lover, JJ wishes ‘at any point in the past three months, we had taken the time to put his bedroom curtains back up.’ There’s a word, used early on, that describes At Certain Points We Touch: crepuscular. Wherever JJ goes, the light isn’t quite clear.

The story draws towards Thomas James and then is repelled from him like the two dancing shadows in the Nauman projection. JJ and Thomas meet up, have wild crazy sex, and argue, at which point JJ disappears across the sea to New York or San Francisco. The American passages are the best part of this story because in America JJ is always with friends. They live off booze and drugs and cheap 24 hour cafe food, off burlesque gigs and cash-in-hand jobs found on internet messageboards. JJ is trying to achieve something, get into the middle of something, but we don’t know what. The spirit of it is warm and indubitable. As JJ says, speaking simply for once: ‘We just knew we were searching for something more than the hand dealt us offered.’

JJ’s return to London is not so much fun. JJ of course has a scene there, centred around a horrible pub called the Joiners. There’s a lovely old guy called Jovian who runs an open mic night and acts as a sort of counsellor to the others (”We told people ridiculous stories, that he was my father, or that we were working together, ghost-writing the memoirs of the last great Warhol starlet, Jackie Jackie Pizza Hut.’) But worries about money and rent are never far from anybody’s mind, and in London Thomas’s dour spectre overshadows everything. JJ begins to exhaust the patience of his friends. The city seems to get smaller and harder as the novel goes on. Street harassment is a fact of life for gay and trans people, and in this book it’s always in the background, easily ignored. Until Thomas’s death, when JJ and Adam meet on a bridge. When Adam starts crying with grief, a group of passing lads laugh at him. It is an evocation of an accepted negativity suddenly really getting to you, and at that moment JJ’s horrible Lancashire childhood suddenly seems a lot closer.

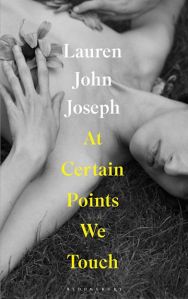

Lauren John Joseph‘s narrative touches upon theoretical physics, the nature of existence and observation, and it’s all very interesting, it all relates to this story of two lovers who, no matter how close they got, could never really know each other, and clearly these lessons are not just for JJ and Thomas. Still, maybe it’s a joke, an irony, but I can’t help wanting Thomas to have been a little more interesting. What the hell, the heart wants what it wants. Unreflexive desire is shot through this novel – either the last of a certain kind of radical writing, or the beginning of something new.

Leave a comment