The Oxbridge education is overrated. Or so it must feel to Hannah Jones. Ten years on from beginning her degree in one of Oxford’s best colleges, she is working in a bookshop, worried about money, pursued by journalists and living with a handsome but distant husband.

The Oxbridge education is overrated. Or so it must feel to Hannah Jones. Ten years on from beginning her degree in one of Oxford’s best colleges, she is working in a bookshop, worried about money, pursued by journalists and living with a handsome but distant husband.

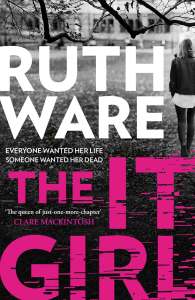

It all held so much promise. Ruth Ware says that ‘writing about Oxford is a particular kind of challenge – it’s been novelised so frequently and so well that it feels slightly hubristic to add to the pile of books about the college experience.’ Yet the Oxford parts of the novel are among some of Ware’s best passages. The students are recognisably 2010s students, modern and idiosyncratic, but they do not seem grafted on to the old-time college with its buildings, landscape, traditions and rules. The relationship between town and college is deftly drawn, and there’s a sense of ancient magic you must have felt if you ever studied at such a place – something that mixes in with the everyday quotidian murmur. This is Hannah getting back to accommodation on a rainy night:

Under the arch of staircase 7 she folded her umbrella, shook off the worst of the water, and made her way slowly up the stairs. Behind each door was a different sound. The silence of study; the laughter of friends congregating; the quiet thump of someone’s music, the volume just slightly too low for Hannah to recognise the song.

Hannah’s time at college was brought to an ugly close by the murder of her best friend, April Clarke-Cliveden. April is the ‘It Girl’ of the title and another of the book’s strengths. There is a tendency in crime fiction to freeze the victims in the moment of their death – the body is found in the prologue, you never get to know them as people, they are basically wall martyrs. But April is a vivid presence throughout. She is vivacious, funny and smart. She is the legendary undergraduate who can go out partying until dawn and still be fresh for the seminar room. When Hannah revisits Oxford ten years later, she finds that their old rooms have been turned into office space. But you can still feel traces of April’s personality there.

April can be arrogant, entitled, even cruel. But there is a heart to her. She puts real effort into her friendship with Hannah – who, frankly, can be a drag and a bore – but April adopts her, encourages confidence in Hannah, builds her up, with no real vested interest in doing so, for no more reason than that she sees things in people. And when April is killed, it’s like part of Hannah dies with her. She retreats to her childhood bedroom, spends years reading letters from her contemporaries, her own drives and ambitions shrinking.

April’s murder is a classic locked room mystery: she is killed in the ‘set’ (a kind of bedsit she shares with Hannah) that has only one way in and out, through the stairwell. A porter named John Neville is convicted of her murder on the strength of Hannah’s testimony – she saw him exit the stairway at the time of her death. Day to day, Neville is an irritation and a creep – he is always messing with Hannah’s head, coming into her room on small pretexts, seeing how far he can push the boundaries. He dies in prison protesting his innocence, and as much as Hannah disliked Neville, she’s always been haunted by the possibility that she sent him to jail, unjustly.

In a murder mystery there must be the sense that things are going on behind the scenes that you don’t know about. The little Pelham college is crowded and incestuous, you think you can see all the betrayals and love triangles that are going on, but it’s unlikely you’ll know the whole truth, not until right at the end. Ware understands how to convey secrets and lies inside small, intelligent groups. The college itself seems to have more secret passages than a Cluedo board. Pelham is walled, but there’s a place you can climb over. There is a fine eerie touch to the stairwell Hannah and April use to get into their building – its lights run on sensors, so after sunset you have to walk, and climb into the dark for a moment, before the light recognises your presence and clicks on.

The It Girl is a long book, perhaps too long, and earnest and ponderous sometimes. But there is a real storytelling engine here, that kicks in so quietly you don’t notice it, then builds to a good, confident pace. Our goody-goody protagonist Hannah has nothing to go on except her intuitions and doubts, and the narrative reflects that, meandering from place to place. But Hannah turns out to be made of stern stuff, and a fine detective in her own right. The end, and how she gets there, is a genuine shocker. Death waits in the garden, but glory is waiting there too.

Leave a comment